Chicago's current mayor, Brandon Johnson, was a fan of defunding the police before he ran for office.

Less than a month after Floyd’s death, the county commissioner from the West Side introduced a nonbinding resolution calling for the county to “redirect funds from policing and incarceration to public services not administered by law enforcement.” The “Justice for Black Lives” resolution was symbolic, but it overwhelmingly passed that July.

“A hundred years from now … the question will be, did we do everything in our power to stand up to systemic racism? Or did we flinch?” Johnson said as he addressed fellow commissioners before the vote. “This will give the county commissioners a road map for taking millions of waste spent on incarceration and policing and reinvesting it.”

The city did in fact cut police staffing by several hundred positions in 2021 (before Johnson ran for mayor) and the results have been entirely predictable.

In 2020 when Floyd's murder in Minneapolis set off a nationwide movement to take resources away from police, the Chicago Police Department had 14,709 full-time positions budgeted and spent $1.76 billion.

The city reduced the police department by 614 positions and cut funding by 2.7% in 2021 in the immediate aftermath of Floyd's murder...

the city reported a 30% increase in crime in 2022. Murders were down 13% from 804 in 2021 to 699 in 2022, but the city stated property crime drove the spike in crime and was up 44% and violent crime was up 1% in 2022 as compared to 2021.

The picture in 2023 was similar. Homicides dropped 15% but robberies were way up, about 40% over the previous year. Aggravated battery and assault were also up.

In February of this year, the city council committed to spending nearly $1 million on a report designed to assess how the city could manage its police staffing problem.

The ordinance approved Monday would give the police department 90 days to identify a “qualified third party” to conduct a “comprehensive staffing analysis.”

That would include “department-wide staffing levels and workforce allocation analysis in every department bureau and unit at every rank, including sworn and civilian members, to help ensure the department has sufficient staffing and efficient workforce allocation.”...

A written report would be required within a year, with a joint committee meeting 30 days after that public release.

The city council has tried this twice before and in both cases the work was never completed and no report was released. But if they don't abandon the effort a third time, we may have a report outlining what the city needs to do sometime next summer. What it will no doubt show is that the city needs more officers to respond to 911 calls. Over the past couple years there have been multiple stories of fights and gunshots and police arriving 30 or more minutes later. We're not talking about a few incidents but tens of thousands of them.

The dysfunction in Chicago continues. This week two 22-year-old female tourists were physically attacked and then knocked to the ground by a group of between eight and ten people around 2 am in the Loop. The criminals left after robbing the women of their valuables. It took the police two hours to show up.

On the same night, another downtown tourist was victimized when five men attacked and robbed him of his cash, jewelry, and phone. The police didn’t arrive for at least three hours.

These cases are just two of the 225,000 urgent Chicago 911 calls with no police available so far this year. That’s about 52 percent of all priority 911 calls in 2023 and far higher than the 19 percent of priority calls that went unanswered in 2019.

Even if the city gets a recommendation for more staffing that everyone can agree on, it's not a sure thing the city can afford it.

Chicago faces a dire police shortage. (See “Can We Get Back to Tougher Policing?,”) Over half of high-priority 911 calls had no cops available to respond. One important reason is that the city is now allocating almost half of its budget to debt and pensions, leaving ever less for essential services, including public safety. The municipal government is acting more like a conduit channeling money from residents to check-collectors than a protector of its citizens’ rights and liberties...

According to the group Truth in Accounting, Chicago continues to live up to its moniker “Second City” in at least one respect: it has the second-worst debt load of any big city in America—about $43,000 per taxpayer, or almost $40 billion in total...

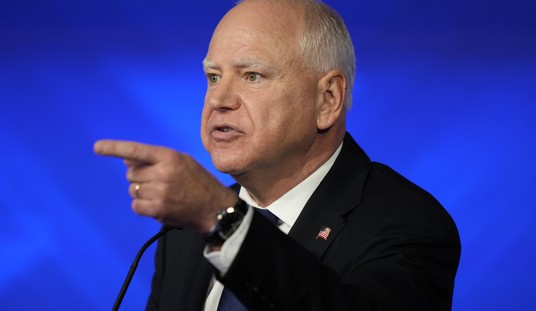

[Mayor] Johnson admitted that property taxes were “painfully high” and in his campaign said that he wouldn’t raise them, instead vowing to “make the suburbs, airlines & ultra-rich pay their fair share.” He wanted to quadruple the transfer levy on expensive property, what he called a “mansion tax,” and impose a transaction tax on Chicago’s tottering finance industry. Much of Johnson’s tax plan either is impossible under existing law or serves more of a punitive than a fund-raising purpose. Illinois governor J. B. Pritzker, no anti-taxer, already said that he would block the financial transfer tax, and voters soundly rejected Johnson’s mansion tax...

The lion’s share of Chicago’s burden is its pension debt, totaling $34 billion, with another $2 billion for retiree health benefits. That is up from just over $20 billion in 2013. Unlike most other places in the United States, Chicago has barely pretended to fund its four major pension plans; it has assets for only about 25 percent of its pension obligations and nothing set aside for health care. It carries the most pension debt of any American city and more than the vast majority of states...

Both Illinois and Chicago tried to reform their pensions beginning in 2014, but two years later, the state supreme court decreed any reductions in vested pensions unconstitutional. This ruling left Chicago with little room for maneuver and led Moody’s to push Chicago’s debt into junk-bond status.

Moody's eventually reversed course thanks to billions of dollars the city received from Biden's American Rescue Plan. But the underlying problems haven't gone away. There's a lot more in the article but the gist is that Chicago is deeply in debt which leaves it very little room to maneuver when it has a problem like rising crime and an insufficient police force.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member