Thursday the Washington Post editorial board published a lengthy piece titled “Wuhan’s early covid cases are a mystery. What is China hiding?” The Post has been pushing for more transparency from China for some time. Last summer they wrote an editorial saying that China’s denial was suspicious. In April of this year the editorial board published another story saying a Chinese lab had identified COVID in December 2019.

This latest editorial takes a specific look at some missing data about the earliest cases in Wuhan. There’s evidence that the official story China provided to the WHO is not the real story.

Josephine Ma, the China news editor of the South China Morning Post, in Hong Kong, reported later that the first patient was a 55-year-old who fell ill on Nov. 17, 2019. Eight more people, from 39 to 79 years old, got sick later in November. Quoting leaked government documents, Ms. Ma found 27 infections by Dec. 15, and 60 by Dec. 20. The total number of cases — mostly retrospectively confirmed either by laboratory tests or clinical diagnosis — had risen to 266 by Dec. 31, including the nine November patients. Her report was published March 13, 2020.

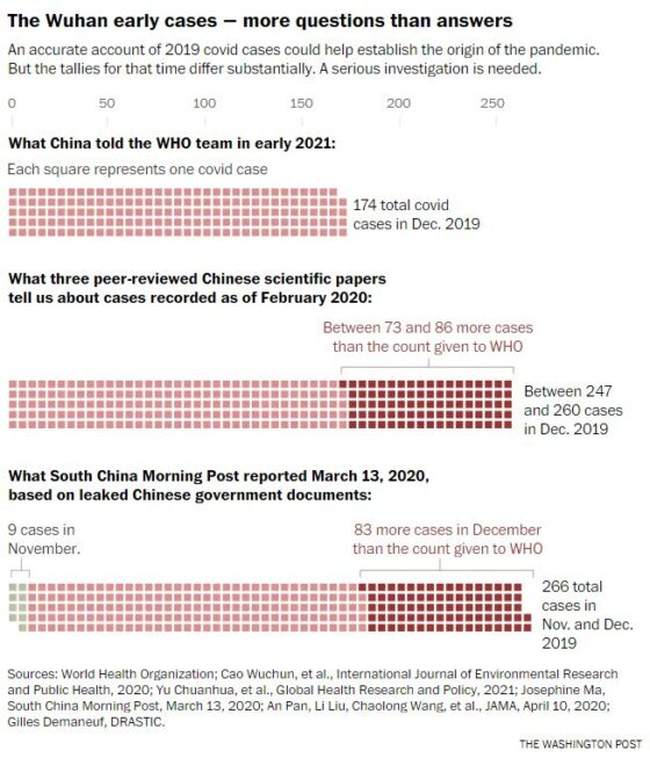

The research group DRASTIC, which has been probing the origins of the virus, has now found evidence that Ms. Ma’s report was right on target. The researchers have determined that by the end of February 2020, China had identified as many as 260 cases from the previous December. Yet China reported to the World Health Organization a year later — in early 2021 — that there were only 174 cases that December. This raises important and still unanswered questions: Who were these early cases? How did they get sick? Why were they not reported to the WHO?

The Post created this graphic which shows the story China has shared with the world compared to other estimates. It appears a lot of the very earliest cases are missing.

China spent much of January lying about the virus’ ability to spread person-to-person. Dr. Li famously tried to warn people on social media and was threatened and forced to recant by the police. Finally on Jan. 20 officials admitted COVID was spreading. Wuhan was locked down three days later.

A year later a team organized by the WHO traveled to Wuhan to investigate the origins of the virus. They asked for information about early cases including the possibility the virus was spreading in October or November.

The WHO team, led by food safety expert Peter Ben Embarek, wanted to know: Were there any earlier cases, say in October or November, that might offer clues to how the pandemic began? In response, the Chinese scientists conducted a search of 233 health institutions in Wuhan, examining 76,253 records of respiratory conditions in the fall of 2019. Only 92 cases were considered possible, but all were excluded after review by the Chinese experts or retrospective testing. The Chinese apparently did not provide original raw data, methods or any independent means for corroboration by the WHO team of these results. The final report concluded that “it is considered unlikely that any substantial transmission” was occurring in October and November.

The joint mission was contentious. Dr. Embarek later said that China had brought heavy pressure on the researchers to not make any mention of a possible laboratory leak as the origin. Eventually, Chinese scientists relented to a statement that such a leak was “extremely unlikely.” But they had provided the visiting WHO team no way to verify such a conclusion. Dr. Embarek also said, after leaving China, that the virus “was circulating widely in Wuhan in December,” suggesting the official 174 cases were only the tip of the iceberg and the virus could have infected 1,000 or more people that month.

Between September of 2020 and May of 2021, three peer-reviewed papers were published, all three of which pointed to there being significantly more COVID cases in December than officially revealed. The figures in these papers were a near match for the leaked figures reported by the South China Morning Post in March 2020.

A paper published in Science this summer argued that the Wuhan wet market was the epicenter of the infection, pointing to zoonotic spillover as the origin. The Post asked Dr. Michael Worobey, one of the authors of that paper, if earlier cases in December or even in November might change his mind.

“With any kind of situation like a SARS-CoV-2 virus that can cause mild or even asymptomatic infection, you’re always taking a sample,” he said. “There’s probably at least 10 times more cases that we haven’t sampled because only something like six percent end up in the hospital. We fully expect the cases that we don’t sample to come from exactly the same geographic distribution as the ones that we do sample.”

But as the Post points out, without knowing where those cases happened it’s impossible to say for certain:

The additional cases could affect the scenario of how the outbreak began, and the timing. The seafood market might have been the point of a zoonotic spillover, but it might also have been the scene of a superspreader event. The incomplete data from China is a serious obstacle for anyone trying to reach a firm conclusion about how the outbreak began.

The Post doesn’t say this but I will: There’s always the possibility that China is effectively lying by hiding from view those cases which might lead to a different conclusion. If there’s one thing we should have learned from all of this it’s that China’s word isn’t to be trusted about anything which has the potential to make China’s one-party state look bad.

The editorial concludes by calling for a new investigation in Wuhan that considers all of the evidence. I don’t think anyone, including the Post really believes that’s likely to happen anytime soon but they are right that given the enormity of the cost of this pandemic, the world should not settle for part of the truth.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member