Last year, during the run-up to the Michigan gubernatorial race, five Republican candidates were dropped from the primary ballot at the last minute, leading to some scrambling by the remaining candidates. The candidates hadn’t been caught in some sort of scandal or criminal situation. They were removed because of problems with the lists of signatures they submitted to qualify for a spot on the ballot. Many of the signatures turned out to be forged or represented names of people who didn’t even exist in the district. Some of the claimed signatories were dead. And now, some states including Colorado and California are investigating and cracking down on the so-called “signature gathering industry.” (NPR)

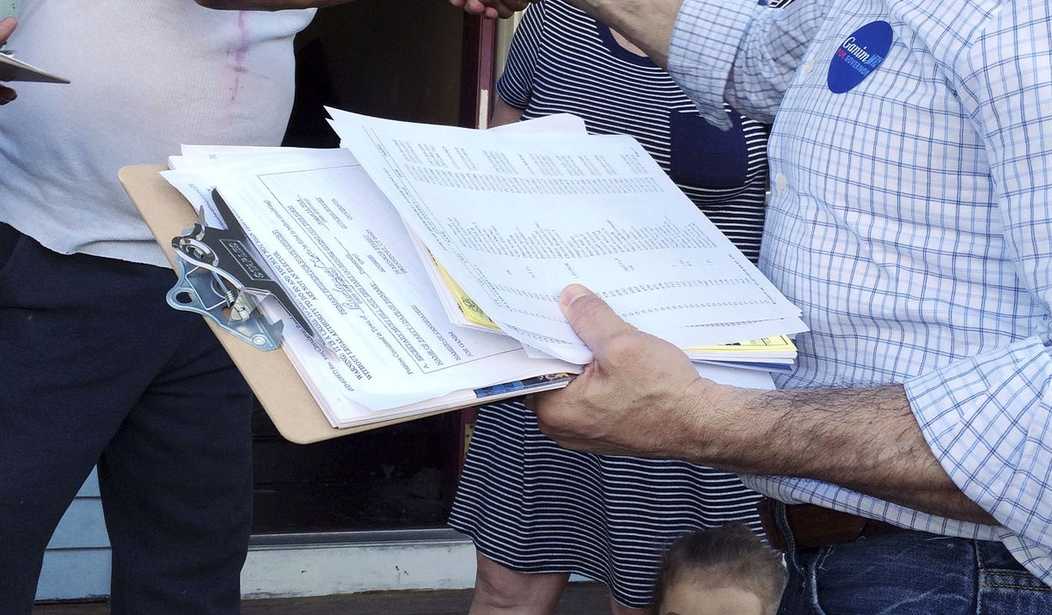

Throughout a large swath of the country, campaigns need to obtain thousands of voter signatures in order to get their candidate or their issue on a ballot.

As a result, campaigns often hire companies to supplement volunteers and do the legwork of compiling signatures.

Jamie Roe, a longtime Republican political strategist in Michigan, tried to get a measure on the state’s ballot last year that would force the legislature to consider new voter ID rules, as well as some new campaign finance laws in the state.

In case you’ve never worked on a political campaign, you should be aware that gathering signatures from the public is a regular and fundamental part of most campaigns. The requirements for how many signatures vary from state to state and for different offices. It’s important work because it’s one of the easiest ways to be tripped up by your opponents. In 2010 I was working on a congressional campaign where our primary opponent wound up being knocked off the ballot after it was discovered that he had been improperly paying signature gatherers. (In New York you can pay such workers by the hour, but not by the signature, which he had been doing.)

Typically, it’s best to have your own volunteers gather signatures because they should (in theory) have the least incentive to cheat. But some offices require huge numbers of signatures and you won’t always have enough volunteers. That’s where these signature-gathering businesses come in. Particularly in states where you can pay by the signature, those workers may have a serious incentive to engage in some fakery.

Also, the price of getting those signatures has been skyrocketing. Jamie Roe, a Republican strategist from Michigan who ran into these problems was interviewed for the linked report. He said that current prices for signatures have reached outrageous levels.

This is particularly frustrating, Roe said, because it was so expensive to get those signatures. He said in the past, a signature from a paid collector would cost him a few dollars. But that’s changed. He said last year signatures cost him upwards of $15 each, which is what he thinks made fraud especially prevalent in Michigan in 2022.

“The thing is, when it’s $2 or $3 per signature, you are probably unlikely to engage in that kind of activity,” he said. “When it’s $15 a signature, there is a high financial motivation to commit fraud.”

Michigan makes it particularly tough. If you want to run for statewide office, you will literally need tens of thousands of signatures collected from people in at least half of the congressional districts in the state. Some states have lower requirements, but every aspiring candidate or group wishing to bring forward a ballot measure will need to deal with this issue sooner or later.

Some improvements to the system are likely in order. The penalties for delivering bogus signatures should be higher. We shouldn’t remove the requirement for signatures entirely because you don’t want a bunch of crackpots with no chance of succeeding demanding space on the ballot. But the minimum requirements in some states could surely be lowered a bit while still ensuring that the candidate can demonstrate some level of popular support.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member