I’m pretty sure most of us were already clued in on this subject despite the almost complete lack of coverage the story receives in the legacy media these days. But now we have a report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington to confirm it. Even as we continue to send literally billions of dollars worth of ammunition, weapons, and other military hardware to Ukraine on a monthly basis, our own military has run critically low on those supplies. In one of many possible bad scenarios looming on the horizon, if we were forced to either go to war against China or even supply Taiwan at a level needed to help them fend off an attack, we would not have enough of a military stockpile to do so. The largest part of the problem comes with our defense companies who produce all of this equipment. They can’t keep up with the demand and it would take quite a while for them to ramp up to the level where they could. (Wall Street Journal, subscription required)

The war in Ukraine has exposed widespread problems in the American armaments industry that may hobble the U.S. military’s ability to fight a protracted war against China, according to a new study.

The U.S. has committed to sending Ukraine more than $27 billion in military equipment and supplies—everything from helmets to Humvees—since Russia’s invasion of the country last year. The infusion of arms is credited with helping the Ukrainian forces blunt Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion in what has become the biggest land war in Europe since World War II.

But the protracted conflict has also exposed the strategic peril facing the U.S. as weapons inventories fall to a low level and defense companies aren’t equipped to replenish them rapidly, according to the study, written by Seth Jones, a senior vice president at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

According to Seth Jones, senior vice president at CSIS, the defense industrial base in the United States is running at its maximum capacity. But that capacity is currently fixed at the peacetime levels we have grown accustomed to. But while the United States isn’t technically at war in Ukraine, we are burning through ammunition and weapons at a wartime pace. This is not a sustainable situation.

In order to weather what Jones describes as “a China-Taiwan Strait kind of scenario,” production capacity would have to increase considerably. Answering critics who counter by saying that we were in Afghanistan for 20 years and didn’t have these issues, he points out the differences between the battlefields. For the last decade of the Afghanistan war, the United States employed a “troop-intensive” strategy. There was fighting on an almost daily basis, but very few sustained pitched battles. There wasn’t all that much of an exchange of missiles and heavy armor, with the troops spending a lot of time looking for smaller pockets of terrorists.

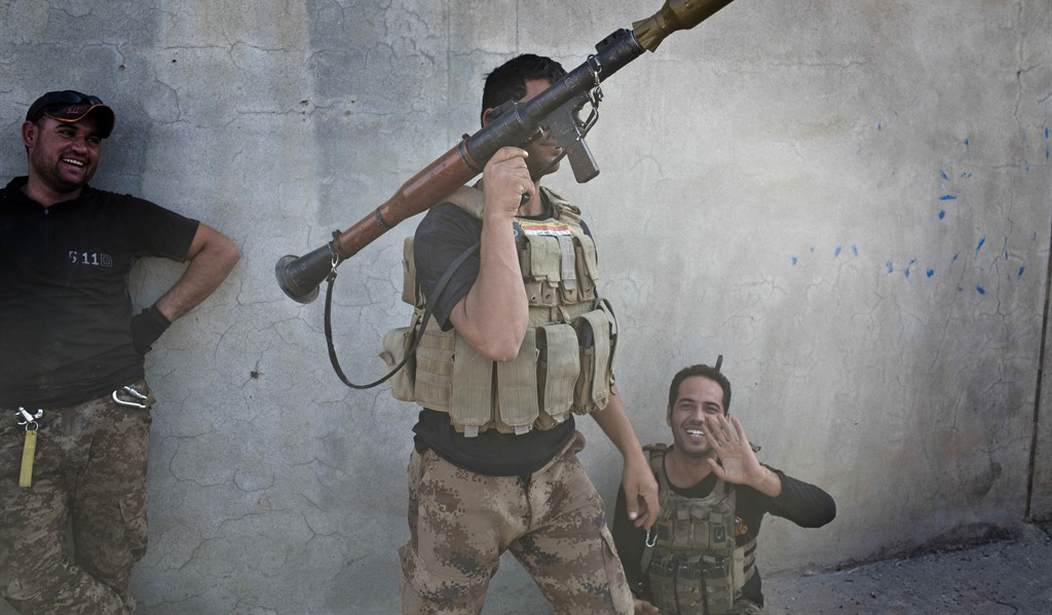

Ukraine is fighting a war far more reminiscent of world war 2, with constant exchanges of rocket fire and air defense weaponry. The consumption rate for ammunition and related hardware is vastly greater. And if China tries to come across the Strait of Taiwan, that will likely be primarily an air and sea battle, also eating up vast numbers of rockets and shells.

The number of Javelin shoulder-fired missiles and antiaircraft Stinger systems we have sent to Ukraine thus far would take seven years each to replenish under current production levels. The same goes for the 155 mm and Howitzer shells we have been shipping to them. In one of the more chilling portions of the CSIS study, they predict that if a similar engagement with China broke out suddenly across the strait, we could begin running out of critical munitions in literally less than a week. And China will be able to hold out for far, far longer than a week. They’ve been stockpiling ammunition and armaments for years without using them for much of anything aside from training exercises and local skirmishes.

The solution is available, assuming the money for the military budget is there. (A big assumption at this point.) The White House would need to start ordering new stockpiles at a pace sufficient to get the defense manufacturers to ramp up their production levels significantly. But they can’t do that overnight and the clock may be ticking. We really should be relying on our NATO partners to start supplying a lot more of what Ukraine needs, but they have relied on us for their defensive needs for so long that they don’t produce much of anything by comparison. We’re in a tenuous position right now, but the people in Congress and at the White House who insist we have to keep supplying Ukraine “for as long as it takes” don’t seem to be willing to do anything about it.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member