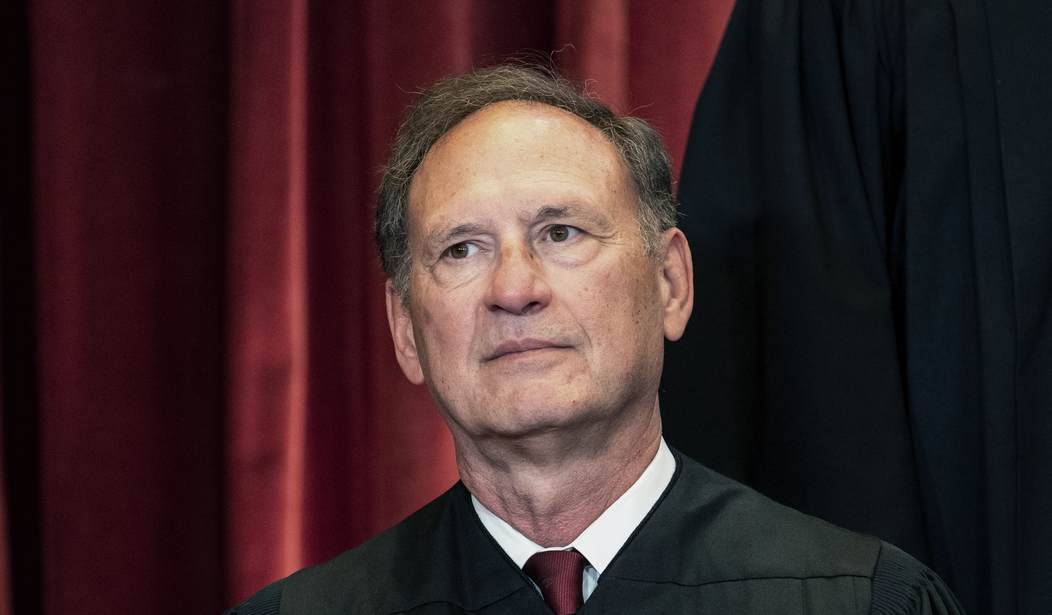

Justice Samuel Alito is ... puzzled. So are Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch. Even Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson can't quite make out what happened, and the decision went nominally in her favor.

In fact, anyone who reads the supposedly "per curiam" order vacating the certiorari writs in Moyle v US and Idaho v US will be puzzled, not least by the claim of "per curiam" attached to multiple attachments of dissent and concurrence by nearly everyone on the court. There seems to be very little consensus behind what happened to this challenge against federal government authority to Idaho's restrictions on abortion. After oral arguments and 46 amicus submissions, not to mention months of deliberation, the court waited until the last minute to Pontius Pilate the case entirely.

[Our VIP and VIP Gold members partner with us to provide the resources for in-depth analysis and commentary such as our SCOTUS end-of-term coverage. Join us in the fight. Become a HotAir VIP member today and use promo code USA60 to receive a 60% discount on your membership. That's a special discount only available for the next 48 hours!]

The Supreme Court had enjoined a lower court order that itself enjoined Idaho from enforcing its new abortion restrictions. That order comes back into effect now, supposedly because the case and the Idaho law (or at least the interpretation by the state) has changed since oral argument. And Alito can't figure out why:

This about-face is baffling. Nothing legally relevant has occurred since January 5. And the underlying issue in this case—whether EMTALA requires hospitals to perform abortions in some circumstances—is a straightforward question of statutory interpretation. It is squarely presented by the decision below, and it has been exhaustively briefed and argued. In addition to the parties’ briefs, we received 46 amicus briefs, including briefs submitted by 44 States and the District of Columbia; briefs expressing the views of 379 Members of Congress; and briefs from prominent medical organizations. Altogether, we have more than 1,300 pages of briefing to assist us, and we heard nearly two hours of argument. Everything there is to say about the statutory interpretation question has probably been said many times over. That question is as ripe for decision as it ever will be. Apparently, the Court has simply lost the will to decide the easy but emotional and highly politicized question that the case presents. That is regrettable.

On this point, but on almost nothing else, Jackson and Alito agree. This is not a wise reconsideration of a hasty writ, Jackson argues, but a gutless retreat:

This Court typically dismisses cases as improvidently granted based on “circumstances . . . which ‘were not . . . fully apprehended at the time certiorari was granted.’” The Monrosa v. Carbon Black Export, Inc., 359 U. S. 180, 183 (1959) (some alterations in original). This procedural mechanism should be reserved for that end—not turned into a tool for the Court to use to avoid issues that it does not wish to decide.

Jackson argues that EMTALA -- the law that the Biden administration is attempting to use to force Idaho hospitals into performing abortions -- speaks for itself and that the case should be adjudicated now. Again, Alito argues the same thing, only for a different conclusion. Alito delves into the congressional history of EMTALA as well as its text, and concludes that nothing within it gives the federal government the authority to contradict state law on abortion. And that was by design, he argues:

For those who find it appropriate to look beyond the statutory text, the context in which EMTALA was enacted reinforces what the text makes clear. Congress designed EMTALA to solve a particular problem—preventing private hospitals from turning away patients who are unable to pay for medical care. H. R. Rep. No. 99–241(I), pt. 1, p. 27 (1985); K. Treiger, Preventing Patient Dumping: Sharpening the COBRA’s Fangs, 61 N. Y. U. L. Rev. 1186, 1188 (1986). And none of many briefs submitted in this suit has found any suggestion in the proceedings leading up to EMTALA’s passage that the Act might also use the carrot of federal funds to entice hospitals to perform abortions. To the contrary, EMTALA garnered broad support in both Houses of Congress, including the support of Members such as Representative Henry Hyde who adamantly opposed the use of federal funds to abet abortion.11

It is also telling that the Congress that initially enacted EMTALA in 1986 and the one that amended it in 1989 also passed appropriations riders under what is now known as the Hyde Amendment (named after Representative Hyde) to prevent federal funds from facilitating abortions, except in limited circumstances. See Harris v. McRae, 448 U. S. 297, 302 (1980). Between 1981 and 1993—the very period when EMTALA was enacted and amended—the Hyde Amendment contained only one exception: for abortions necessary to save the life of the pregnant woman. Congressional Research Service, E. Liu & W. Shen, The Hyde Amendment: An Overview 1 (2022); see §204, 99 Stat. 1119 (1986 Hyde Amendment). The Hyde Amendment thus prohibited federal funds from paying for the health-related abortions that the Government says EMTALA mandates. It would have been strange indeed if a Congress that repeatedly sought to prevent federal funding of abortions simultaneously enacted a law that, as interpreted by the Government, requires hospitals and physicians to perform that very same procedure.

Furthermore, as Alito notes, EMTALA is a funding bill rather than just plain regulation. The threat involved here is that Biden's HHS can withhold these funds unless Idaho complies with their interpretation of EMTALA. That, however, triggers a requirement that the funding prerequisites be "unambiguous" rather than interpretive:

First, consider the requirement that EMTALA speak unambiguously. Even if it were possible to read EMTALA as requiring abortions prohibited by Idaho law, it is beyond dispute that such a requirement is not unambiguously clear. The statute does not mention abortion, let alone expressly bind hospitals to perform abortions contrary to state law.

The need for clear statutory language is especially important in this suit because the Government’s interpretation would intrude on an area traditionally left to state control, namely, the practice of medicine. We typically expect Congress to “‘make its intention “clear and manifest” if it intends to pre-empt the historic powers of the States.’” Gregory v. Ashcroft, 501 U. S. 452, 461 (1991) (quoting Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 U. S. 218, 230 (1947)); see also Gonzales v. Oregon, 546 U. S. 243, 274 (2006) (“[T]he background principles of our federal system also belie the notion that Congress would use such an obscure grant of authority to regulate areas traditionally supervised by the States’ police power”).

Second, consider the requirement that parties be given a choice before being bound by Spending Clause conditions. The Government’s interpretation purports to limit Idaho’s choices about what conduct to criminalize. But Idaho never “agree[d]” to be bound by EMTALA,14 Cummings, 596 U. S., at 219, let alone to surrender its historic power to regulate the practice of medicine or the performance of abortions within its borders.

Both Jackson and Alito go on at length over their arguments. Take them or leave them as you will, but they do demonstrate one thing: this issue is both ripe and well considered. So why didn't the court just settle the issue now, rather than allow the fight to continue and wait for it to return in pretty much the same shape as it currently stands?

The impression this leaves is that a majority of justices don't want to weigh in on abortion again unless absolutely no other option is at hand. That's hardly courageous, and it's not just, either. For all of the parties involved.

Addendum: Tomorrow had been the last scheduled day for publication of opinions, but it appears the court will add another day next week. Two other opinions got handed down today -- a stay order on the EPA in a fight over an interpretation of the "good neighbor" clause of the Clean Air Act, and the vacating of the bankruptcy of Purdue Pharma over the opioid settlement. The Sackler family got excluded from that settlement without declaring bankruptcy themselves, and today's court ruled that the statute doesn't grant court that authority. We may have more on that one later.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member