Anyone want to take bets on the life expectancy of the Chevron doctrine after today’s unanimous decision on Sackett v EPA? The Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the EPA had grossly overstepped its congressional mandate in defining “Waters of the United States,” vastly limiting its authority to declare jurisdiction over what it claims to be “wetlands” on private property.

It’s the second such loss in as many years for the EPA’s attempt to aggrandize its jurisdiction, CBS News notes:

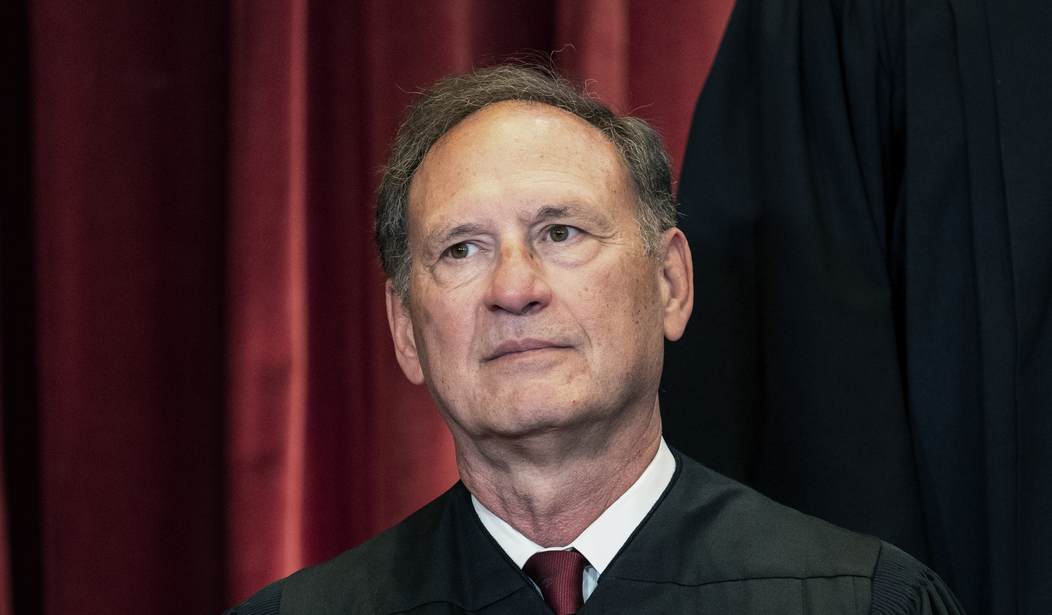

In an opinion authored by Justice Samuel Alito in the case known as Sackett v. EPA, the high court found that the agency’s interpretation of the wetlands covered under the Clean Water Act is “inconsistent” with the law’s text and structure, and the law extends only to “wetlands with a continuous surface connection to bodies of water that are ‘waters of the United States’ in their own right.”

Five justices joined the majority opinion by Alito, while the remaining four — Justices Brett Kavanaugh, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson — concurred in the judgment.

The decision from the conservative court is the latest to target the authority of the EPA to police pollution. On the final day of its term last year, the high court limited the agency’s power to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants, dealing a blow to efforts to combat climate change.

In both instances, the EPA had tried to extend its authority without involving Congress. In this case, which has been percolating for years, the Obama-era EPA had defined the term “wetland” in the Clean Water Act and Waters of the US rule (WOTUS) as basically any land where water naturally pooled on occasion. That led the EPA in 2004 to block Mike and Chantell Sackett from completing a home on their residential-zoned Idaho lot of less than an acre and socking them with massive per-day fines until they dismantled what had already been built — even though their land was nowhere near a navigable body of water, as the WOTUS rule required. I wrote about this in 2011 when the Sacketts first went to the Supreme Court for relief, only to see the case punted on the core question in that term. They did strike down the EPA’s fines, but did not rule on the validity of their claim to jurisdiction over the Sackett’s so-called “wetland.”

Eleven years later, the Supreme Court finally and unanimously acted, although four justices didn’t want to use the case to set precedent. This time the court has set a clear definition for “waters of the United States” in relation to EPA jurisdiction, and ruled that it has to be limited to bodies of water with consistent and permanent connection to navigable bodies of water that would otherwise also fall under federal jurisdiction. Justice Samuel Alito wrote the controlling and precedential opinion:

First, this Court “require[s] Congress to enact exceedingly clear language if it wishes to significantly alter the balance between federal and state power and the power of the Government over private property.” United States Forest Service v. Cowpasture River Preservation Assn., 590 U. S. ___, ___–___ (2020) (slip op., at 15–16); see also Bond, 572 U. S., at 858. Regulation of land and water use lies at the core of traditional state authority. See, e.g., SWANCC, 531 U. S., at 174 (citing Hess v. Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corporation, 513 U. S. 30, 44 (1994)); Tarrant Regional Water Dist. v. Herrmann, 569 U. S. 614, 631 (2013). An overly broad interpretation of the CWA’s reach would impinge on this authority. The area covered by wetlands alone is vast—greater than the combined surface area of California and Texas. And the scope of the EPA’s conception of “the waters of the United States” is truly staggering when this vast territory is supplemented by all the additional area, some of which is generally dry, over which the Agency asserts jurisdiction. Particularly given the CWA’s express policy to “preserve” the States’ “primary” authority over land and water use, §1251(b), this Court has required a clear statement from Congress when determining the scope of “the waters of the United States.” SWANCC, 531 U. S., at 174; accord, Rapanos, 547 U. S., at 738 (plurality opinion).

The EPA, however, offers only a passing attempt to square its interpretation with the text of §1362(7), and its “significant nexus” theory is particularly implausible. It suggests that the meaning of “the waters of the United States” is so “broad and unqualified” that, if viewed in isolation, it would extend to all water in the United States. Brief for Respondents 32. The EPA thus turns to the “significant nexus” test in order to reduce the clash between its understanding of “the waters of the United States” and the term defined by that phrase, i.e., “navigable waters.” As discussed, however, the meaning of “waters” is more limited than the EPA believes. See supra, at 14. And, in any event, the CWA never mentions the “significant nexus” test, so the EPA has no statutory basis to impose it. See Rapanos, 547 U. S., at 755–756 (plurality opinion).

Not only do they not have that authority, the test and the EPA’s application of it is so arbitrary that no one can possibly know for sure where it applies. Since the Clean Water Act has both criminal and civil penalties, that ambiguity itself is unconstitutional, not to mention unfounded in the EPA’s statutory authorization, Alito writes:

Second, the EPA’s interpretation gives rise to serious vagueness concerns in light of the CWA’s criminal penalties. Due process requires Congress to define penal statutes “‘with sufficient definiteness that ordinary people can understand what conduct is prohibited’” and “‘in a manner that does not encourage arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement.’” McDonnell v. United States, 579 U. S. 550, 576 (2016) (quoting Skilling v. United States, 561 U. S. 358, 402–403 (2010)). Yet the meaning of “waters of the United States” under the EPA’s interpretation remains “hopelessly indeterminate.” Sackett, 566 U. S., at 133 (ALITO, J., concurring); accord, Hawkes Co., 578 U. S., at 602 (opinion of Kennedy, J.).

The EPA contends that the only thing preventing it from interpreting “waters of the United States” to “conceivably cover literally every body of water in the country” is the significant-nexus test. Tr. of Oral Arg. 70–71; accord, Brief for Respondents 32. But the boundary between a “significant” and an insignificant nexus is far from clear. And to add to the uncertainty, the test introduces another vague concept—“similarly situated” waters—and then assesses the aggregate effect of that group based on a variety of open-ended factors that evolve as scientific understandings change. This freewheeling inquiry provides little notice to landowners of their obligations under the CWA. Facing severe criminal sanctions for even negligent violations, property owners are “left ‘to feel their way on a case-by-case basis.’” Sackett, 566 U. S., at 124 (quoting Rapanos, 547 U. S., at 758 (ROBERTS, C. J., concurring)). Where a penal statute could sweep so broadly as to render criminal a host of what might otherwise be considered ordinary activities, we have been wary about going beyond what “Congress certainly intended the statute to cover.” Skilling, 561 U. S., at 404.

Under these two background principles, the judicial task when interpreting “the waters of the United States” is to ascertain whether clear congressional authorization exists for the EPA’s claimed power. The EPA’s interpretation falls far short of that standard.

Alito then sets the definition of “waters of the United States” and the jurisdiction of the Clean Water Act in relatively clear and precise terms:

In sum, we hold that the CWA extends to only those “wetlands with a continuous surface connection to bodies that are ‘waters of the United States’ in their own right,” so that they are “indistinguishable” from those waters. Rapanos, 547 U. S., at 742, 755 (plurality opinion) (emphasis deleted); see supra, at 22. This holding compels reversal here. The wetlands on the Sacketts’ property are distinguishable from any possibly covered waters.

It took nineteen years for common sense to prevail. God bless the Sacketts, who have persevered for justice for two decades against a bureaucracy that values power over the rule of law, and against a Congress that couldn’t be bothered to rein in an out-of-control agency it authorizes. Even the four justices that didn’t want to reach a precedential definition of WOTUS at least recognized the injustice involved in the EPA’s lawless application of its ambiguous “nexus” test.

So what’s next? The Supreme Court has taken up a case for next term, Loper Bright, that challenges the Chevron doctrine requiring courts to defer to federal agencies for definition of terms and application of rules. This court appears far more skeptical than ever about federal agencies and their “definitions” when it comes to setting their own authority and jurisdictions. Sackett yanked that chain back on the EPA; Loper Bright might do the same for the entire federal bureaucracy.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member