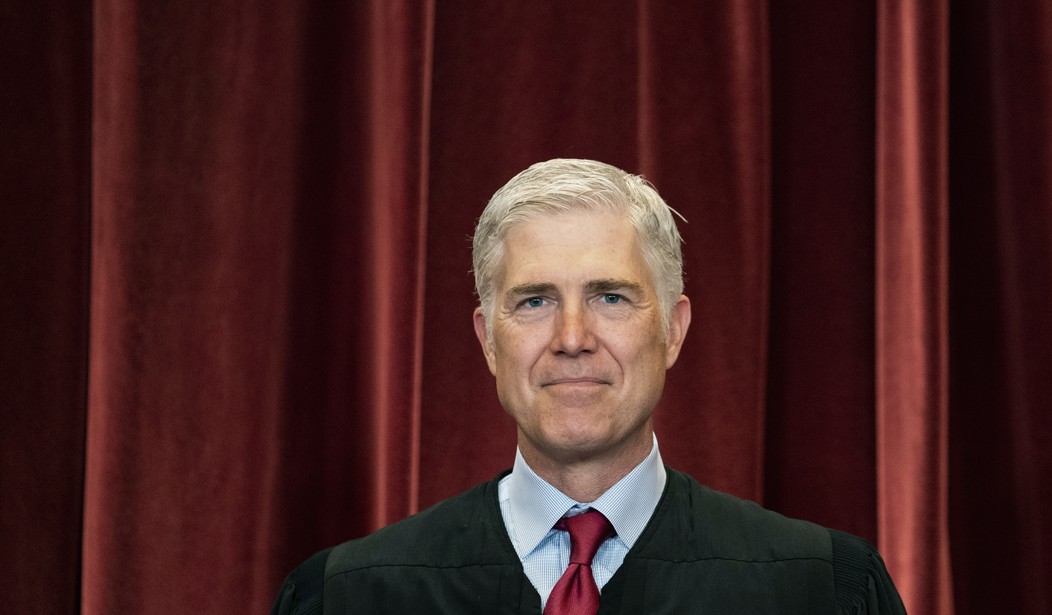

And that’s a very good question, especially after key decisions from a conservative Supreme Court majority on wide-ranging hot-button issues. People on the Right and especially border states celebrated the court’s extension of Title 42 border restrictions in yesterday’s 5-4 ruling, but Justice Neil Gorsuch broke with his fellow conservatives. It looks like Gorsuch joined the liberal wing, but in this case, looks are entirely deceiving.

Karen covered it yesterday, especially the immediate impact of the decision, but added that “Gorsuch is right” in his objection. It’s worth exploring why, and what this does to the principles underpinning decisions like Dobbs, Bruen, Alabama Association of Realtors, and other cases celebrated on the Right.

First, let’s read all of what Gorsuch had to say in his objection to the stay in Arizona v Mayorkas that kept the emergency policy of Title 42 in place. It’s brief enough to include the dissent in its entirety here, emphasis mine:

From March 2020 to April 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention responded to the COVID–19 pandemic by issuing a series of emergency decrees. Those decrees—often called “Title 42 orders”—severely restricted immigration to this country on the ground that it posed a “serious danger” of “introduc[ing]” a “communicable disease.” 58 Stat. 704, 42 U. S. C. §265. Fast forward to a few weeks ago. A district court held that the Title 42 orders were arbitrary and capricious, vacated them, and enjoined their operation. On appeal, Arizona and certain other States moved to intervene to challenge the district court’s ruling, arguing that the federal government would not defend the Title 42 orders as vigorously as they might. The D. C. Circuit denied the States’ motion. In response, the States have now come to this Court seeking two things. First, the States ask us to grant expedited review of the D. C. Circuit’s intervention ruling. Second, the States ask us to stay the district court’s judgment while we review the D. C. Circuit’s intervention ruling. This stay would effectively require the federal government to continue enforcing the Title 42 orders indefinitely. Today, the Court obliges both requests. Respectfully, I believe these decisions unwise.

Reasonable minds can disagree about the merits of the D. C. Circuit’s intervention ruling. But that case-specific decision is not of special importance in its own right and would not normally warrant expedited review. The D. C. Circuit’s intervention ruling takes on whatever salience it has only because of its presence in a larger underlying dispute about the Title 42 orders. And on that score, it is unclear what we might accomplish. Even if at the end of it all we find that the States are permitted to intervene, and even if the States manage on remand to demonstrate that the Title 42 orders were lawfully adopted, the emergency on which those orders were premised has long since lapsed. In April 2022, the federal government terminated the Title 42 orders after determining that emergency immigration restrictions were no longer necessary or appropriate to address COVID–19. 87 Fed. Reg. 19944. The States may question whether the government followed the right administrative steps before issuing this decision (an issue on which I express no view). But they do not seriously dispute that the public-health justification undergirding the Title 42 orders has lapsed. And it is hardly obvious why we should rush in to review a ruling on a motion to intervene in a case concerning emergency decrees that have outlived their shelf life.

The only plausible reason for stepping in at this stage that I can discern has to do with the States’ second request. The States contend that they face an immigration crisis at the border and policymakers have failed to agree on adequate measures to address it. The only means left to mitigate the crisis, the States suggest, is an order from this Court directing the federal government to continue its COVID-era Title 42 policies as long as possible—at the very least during the pendency of our review. Today, the Court supplies just such an order. For my part, I do not discount the States’ concerns. Even the federal government acknowledges “that the end of the Title 42 orders will likely have disruptive consequences.” Brief in Opposition for Federal Respondents 6. But the current border crisis is not a COVID crisis. And courts should not be in the business of perpetuating administrative edicts designed for one emergency only because elected officials have failed to address a different emergency. We are a court of law, not policymakers of last resort.

This to me is the key point — one that undergirds practically every major Supreme Court decision over the last two years. First off, though, let’s stipulate that the outcome of this stay will benefit the border states and the US more generally. In the middle of a border crisis that Joe Biden fomented and Congress refuses to address, keeping Title 42 restrictions in place will prevent the crisis from getting worse. This won’t improve the status quo for the border states, but at least it stops the situation from getting dramatically worse. Conservatives cheered that outcome, and for good reason — in the short term.

In the long run, though, this puts the Supreme Court right back to its position that produced decisions like Roe and Obergefell. Those were also outcome-based decisions that amounted to legislative activity and policy-setting as well. At the time, the courts noted that the constitutional process for crafting policy on these important social issues didn’t work, so it arrogated the role of becoming “policymakers of last resort,” which this very same Supreme Court explicitly rejected in the Dobbs decision just a few months ago. Justice Samuel Alito insisted in that decision that the Constitution did not address abortion, and so the Supreme Court could not be expected to weigh it, let alone continue to craft policy on access to it.

And in this case, it’s not just that the issue is unaddressed in federal law. Title 42 exists in federal law (Section 262 of U.S. Code Title 42), which gives the executive branch authority to block entry to the US over risks of mass spread of communicable disease. This clearly was the concern in 2020 and 2021 in the pandemic, but the pandemic is over and so is the risk. Conservatives in particular emphasize that in relation to CDC authority to issue other rules, such as mask and vaccine mandates, and they are correct to do so.

Without an acute emergency, the CDC can’t invoke Title 42 restrictions. At the moment, Title 42 is being left in place not for a health emergency but to deal with a policy and executive-branch enforcement failure. Congress could solve this by passing legislation to make Title 42 apply generally without any acute health emergency, but they haven’t and aren’t likely to do so over the next two years — if ever. Based on the law, the continued use of Title 42 should have ended months ago — and the court should not have forced it to remain in place.

Essentially, the court just took the opposite position in its double rejection of eviction moratoria promulgated by the CDC and the Biden administration. Remember that? The Supreme Court ruled — correctly — that the CDC and the executive branch lacked the authority for those orders. The Biden administration warned that the outcome would result in mass evictions, which so far has not come to pass. The court rejected that argument both specifically and in principle in John Roberts’ ruling, arguing that Congress needed to act to provide that authority before the court could recognize it.

By opting for the outcome-based argument in this case, Gorsuch correctly concludes, the court has once again assumed its arrogation of policymaking authority. It completely undermines the principles outcomes in Bruen, Dobbs, and several other cases in which judicial restraint had been restored.

Granted, this is a temporary stay, and the court may well reach that conclusion when this case is finally decided. However, their abandonment of the law in this instance undermines their ability to argue that policy outcomes don’t matter when deciding this case in particular, and other cases more generally. The refusal to apply that principle in a case where the outcome is disfavorable to their perceived political interests makes it unclear how or why they would apply the principle in their ultimate ruling when the outcome would be exactly the same. And that lack of applied principle leaves the distinct impression that earlier rulings were less about principle and more about perceived outcomes, too.

That may be many things, but judicial restraint it ain’t.

That’s what makes Ketanji Brown Jackson’s decision to join Gorsuch’s dissent either hopeful or wildly amusing. Gorsuch clearly isn’t on the “liberal side” on Title 42, but occupying a more principled conservative line. Neither of the other two liberal justices, Elena Kagan nor Sonia Sotomayor, signed up for Gorsuch’s dissent for that reason. If Jackson really endorses judicial restraint and is using this case to signal that, then all the better. But if not, then her attempt to piggy-back on Gorsuch in this dissent will look mighty foolish when she eventually backs judicial-activist outcomes. Like this one.