This decision by the Fifth Circuit is, to quote our current president, a “big f***ing deal.” And that’s not just because it vindicates Republican opposition to the structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Board, although it certainly does that. And it’s not just because it dismantles — for now — a bad policy that the CFPB was pushing at the moment, although it does do that, too.

No, this decision has far-reaching consequences in reminding everyone that the executive branch and its subordinate agencies cannot constitutionally generate its own funding separate from Congress. And that will be a very big f***ing deal in a matter just getting into the courts at the moment:

A federal appeals court found the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is funded through an unconstitutional method, a ruling that threw out the agency’s regulation on payday lenders and struck a blow against how the agency operates.

The decision, by a three-judge panel of the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans, found the CFPB’s funding structure violated the Constitution’s doctrine of separation of powers, which sets the authority of the three branches of government. Congress has the sole power of the federal purse, and the bureau’s funding structure undercuts that authority, the court said.

When Congress created the CFPB through the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial overhaul law, it exempted the agency from the annual legislative appropriations process. Rather than having Congress review and vote on its budget, the bureau gets its money through transfers from the Federal Reserve, up to a certain cap. The Fed can’t turn down requests under that cap.

“Congress’s decision to abdicate its appropriations power under the Constitution, i.e., to cede its power of the purse to the Bureau, violates the Constitution’s structural separation of powers,” Judge Cory Wilson wrote for the court. All three judges on the panel were appointed by former President Donald Trump.

Why did Democrats structure the CFPB’s financing in that manner in the first place? They knew that Republicans would defund the CFPB when they had enough control of Washington again. This funding mechanism essentially made the CFPB “a fourth branch of government,” as retiring Sen. Ben Sasse put it in a statement yesterday celebrating the decision. The only way to eliminate funding for the CFPB would have been to repeal it by statute, and Democrats would have blocked such an effort in the Senate through the filibuster.

No other agency has that kind of autonomy from Congress. Constitutionally speaking, the CFPB — or at least its funding — is an abomination to the concept of checks and balances. Elizabeth Warren and her allies explicitly designed it to be free of any sort of accountability, an expression of (Woodrow) Wilsonian rule-by-elites that is extreme even in a bureaucracy long operating for its own benefit and purposes rather than under the strict control of elected officials in the legislature.

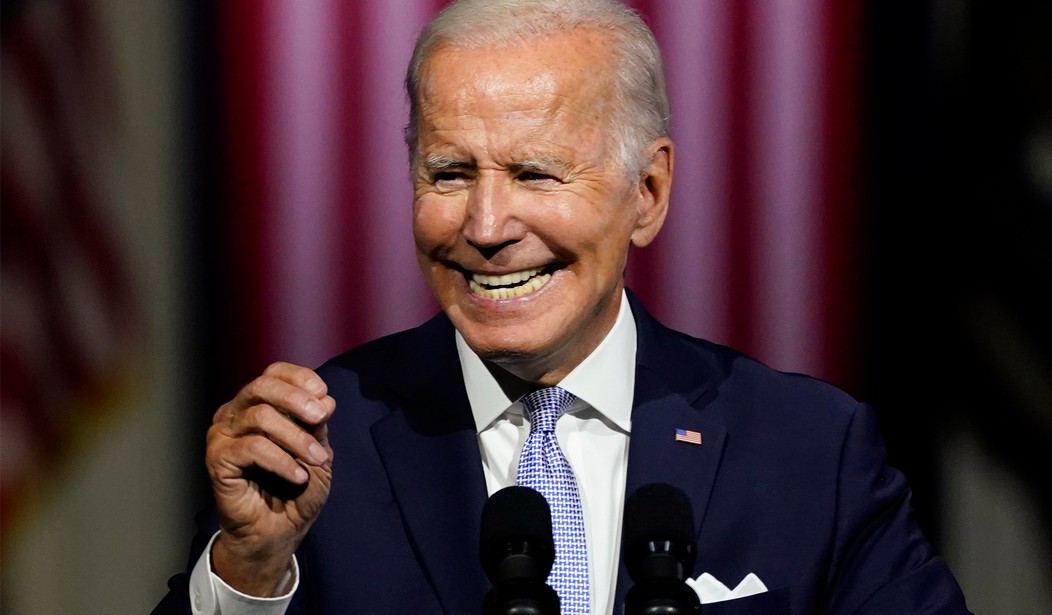

However, it’s not the only example of such arrogance. In August, Joe Biden announced that he would unilaterally forgive student loans, committing several hundred billion dollars to buying it out without any authorization or appropriation from Congress. This decision sends a shot across Biden’s bow on his Academia bailout, especially since at least one of the lawsuits against it will take place in the Fifth Circuit’s jurisdiction in Texas.

Judge Cory Wilson’s logic in dismantling the CFPB’s autonomy clearly applies directly to the core issue in Biden’s loan-forgiveness plan:

Drawing on the British experience, the Framers “carefully separate[d] the ‘purse’ from the ‘sword’ by assigning to Congress and Congress alone the power of the purse.” Tex. Educ. Agency v. U.S. Dep’t of Educ., 992 F.3d 350, 362 (5th Cir. 2021). 8 The Framers’ reasoning was twofold. First, they viewed Congress’s exclusive “power over the purse” as an indispensable check on “the overgrown prerogatives of the other branches of the government.” The Federalist No. 58 (J. Madison). Indeed, “the separation of purse and sword was the Federalists’ strongest rejoinder to Anti-Federalist fears of a tyrannical president.” Josh Chafetz, Congress’s Constitution, Legislative Authority and the Separation of Powers 57 (2017).

The Framers also believed that vesting Congress with control over fiscal matters was the best means of ensuring transparency and accountability to the people. …

The text of the Constitution reflects these foundational considerations. First, even before enumerating how legislation becomes law (i.e., passage by both houses of Congress and presentment to the President for signature), the Constitution provides that “[a]ll Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives . . . .” U.S. Const. art. I, § 7, cl. 1. It then grants the general authority “[t]o lay and collect Taxes” and spend public funds for various ends—the first power positively granted to Congress by the Constitution. Id. art. I, § 8, cl. 1. Importantly though, that general grant of spending power is cabined by the Appropriations Clause and its follow-on, the Public Accounts Clause: “No money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law; and a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time.”

The Appropriations Clause’s “straightforward and explicit command” ensures Congress’s exclusive power over the federal purse. OPM v. Richmond, 496 U.S. 414, 424 (1990). Critically, it makes clear that “[a]ny exercise of a power granted by the Constitution to one of the other branches of Government is limited by a valid reservation of congressional control over funds in the Treasury.” Id. at 425. Of equal importance is what the clause “takes away from Congress: the option not to require legislative appropriations prior to expenditure.” Kate Stith, Congress’ Power of the Purse, 97 Yale L.J. 1343, 1349 (1988). Given that the executive is forbidden from unilaterally spending funds, the actual exercise by Congress of its power of the purse is imperative to a functional government. The Appropriations Clause thus does more than reinforce Congress’s power over fiscal matters; it affirmatively obligates Congress to use that authority “to maintain the boundaries between the branches and preserve individual liberty from the encroachments of executive power.” All Am. Check Cashing, 33 F.4th at 231 (Jones, J., concurring). …

Justice Scalia similarly observed that, while the requirement that funds be disbursed in accord with Congress’s dictate and Congress’s alone may be inconvenient, “clumsy,” or “inefficient,” it “reflect[s] ‘hard choices . . . consciously made by men who had lived under a form of government that permitted arbitrary governmental acts to go unchecked.’” NLRB v. Noel Canning, 573 U.S. 513, 601–02 (2014) (Scalia, J., concurring) (quoting INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919, 959 (1983)). In short, the Appropriations Clause expressly “was intended as a restriction upon the disbursing authority of the Executive department.” Cincinnati Soap Co. v. United States, 301 U.S. 308, 321 (1937).

Given the highly controversial nature of Biden’s bailout, this looks like a serious effort at throat-clearing by the Fifth Circuit at this particular moment in time. Biden’s loan forgiveness plan explicitly violates everything Judge Wilson writes about the constitutional framework dealing with appropriations and disbursement.

And in the case of Biden’s unilateral declaration, the crisis is even more acute. The CFPB’s structure threatened to make it a fourth branch of government with no accountability to the other three. Biden’s action threatens to effectively reduce government to one branch — the executive — by ending Congress’ “exclusive power over the federal purse.” That would be the biggest f***ing deal in constitutional order since the Civil War, if not in the history of the United States, triggered by a demented fool who wanted to buy votes in an election.

Let’s hope that the plaintiffs in these lawsuits against Biden’s Academia bailout take a page from CFSAA v CFPB and make that point explicitly in their arguments — especially in the Fifth Circuit’s jurisdiction. And soon.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member