What constitutes “navigable waters”? That question has bedeviled Mike and Chantell Sackett for 15 years, and now it comes back again to the Supreme Court. Ten years ago, the Supreme Court took an incremental approach to the Waters of the United States (WOTUS) Act and the EPA’s regulation based on its jurisdiction over “navigable waters.”

With the EPA still blocking the Sacketts from building a house on their own land, a very different Supreme Court has taken the case back up again. This time, the Washington Post notes, they will likely aim higher than the Administrative Procedure Act (APA):

The justices said Monday that they will consider, probably in the term beginning in October, a long-running dispute involving an Idaho couple who already won once at the Supreme Court in an effort to build a home near Priest Lake. The Environmental Protection Agency says there are wetlands on the couple’s roughly half-acre lot, which brings it under the jurisdiction of the Clean Water Act, and thus requires a permit.

The case raises the question of the test that courts should use to determine what constitutes “waters of the United States,” which the Clean Water Act was passed to protect in 1972.

In a 2006 case called Rapanos v. U.S., the court could not muster a majority opinion. Four justices, led by Justice Antonin Scalia, said the provision means water on the property in question must have a connection to a river, lake or other waterway.

But a fifth justice, Anthony M. Kennedy, created the test that emerged from the case, saying the act covers wetlands with a “significant nexus” to those other bodies of water.

This isn’t the only environmental-regulation case for which the Supreme Court has granted cert, the Post’s Climate 202 frets:

The order was the latest indication that the conservative majority on the Supreme Court is stepping in to assess the limits of the nation’s bedrock environmental laws — potentially in ways that hamstring President Biden’s environmental agenda.

It comes as the justices are poised to hear oral arguments in February in cases challenging the Environmental Protection Agency’s authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired power plants.

“It seems like we have a new conservative supermajority on the court that is much more inclined to do a slash-and-burn expedition through our major environmental laws,” Robert Percival, who directs the University of Maryland’s environmental law program, told The Climate 202. …

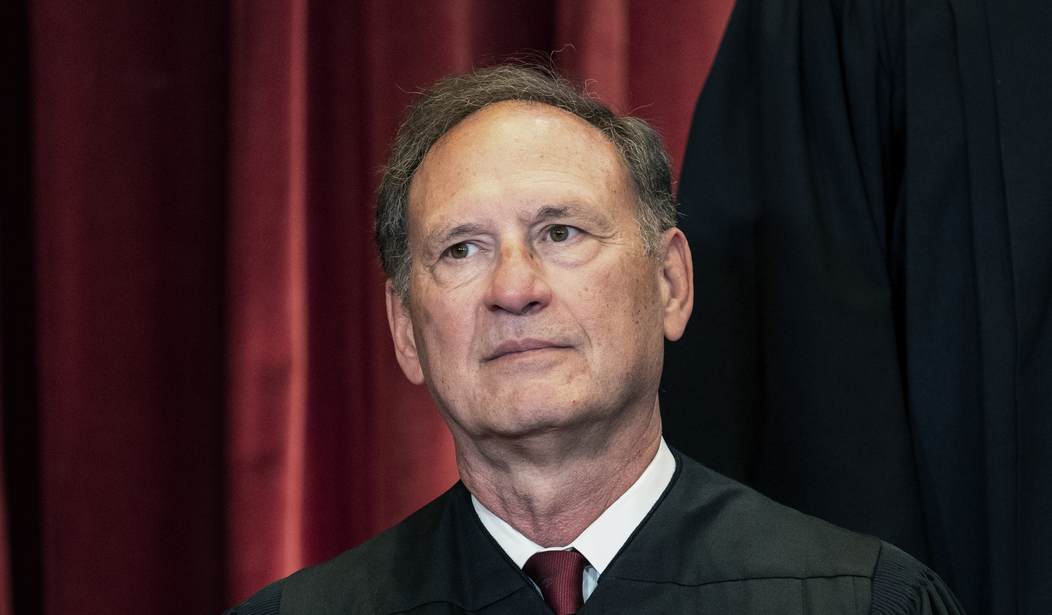

Mark Ryan, a Clean Water Act expert who worked as a lawyer at the EPA for 24 years, told The Climate 202 that he thinks at least five members of the court’s conservative majority — Justices Samuel A. Alito Jr., Amy Coney Barrett, Neil M. Gorsuch, Brett M. Kavanaugh and Clarence Thomas — could vote to adopt Scalia’s narrower test.

“There are at least five justices who are skeptical of giving agencies too much authority,” Ryan said.

Well, yes, and the saga of the Sacketts explains why. The ruling ten years ago clearly rebuked the EPA for its attempts to fine the Sacketts into submission and force them to demolish the house that they had already begun to build before the agency informed them of their wetlands finding. Despite the clear signal sent by the unanimous decision in 2012, the EPA has still battled the Sacketts over the use of their two-thirds acre of land with the argument that a house would somehow impair “navigable waters.” Justice Samuel Alito warned Congress to remove the ambiguities around that term and settle on a reliable definition soon:

Real relief requires Congress to do what it should have done in the first place: provide a reasonably clear rule regarding the reach of the Clean Water Act. When Congress passed the Clean Water Act in 1972, it provided that the Act covers “the waters of the United States.” 33 U. S. C. §1362(7). But Congress did not define what it meant by “the waters of the United States”; the phrase was not a term of art with a known meaning; and the words themselves are hopelessly indeterminate. Unsurprisingly, the EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers interpreted the phrase as an essentially limitless grant of authority. We rejected that boundless view, see Rapanos v. United States, 547 U. S. 715, 732–739 (2006) (plurality opinion); Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook Cty. v. Army Corps of Engineers, 531 U. S. 159, 167–174 (2001), but the precise reach of the Act remains unclear. For 40 years, Congress has done nothing to resolve this critical ambiguity, and the EPA has not seen fit to promulgate a rule providing a clear and sufficiently limited definition of the phrase. Instead, the agency has relied on informal guidance. But far from providing clarity and predictability, the agency’s latest informal guidance advises property owners that many jurisdictional determinations concerning wetlands can only be made on a case-by-case basis by EPA field staff. See Brief for Competitive Enterprise Institute as Amicus Curiae 7–13.

Allowing aggrieved property owners to sue under the Administrative Procedure Act is better than nothing, but only clarification of the reach of the Clean Water Act can rectify the underlying problem.

Neither the EPA nor Congress has lifted a finger to provide a reliable and sufficiently determinate definition that limits EPA authority in any meaningful way. The Sacketts have spent another decade fighting the same issue even after that unanimous SCOTUS decision. The Pacific Legal Foundation continues to represent them in this fight and adamantly want the court to rule once and for all on either a proper definition of “navigable waters” or to strike down the WOTUS Act entirely:

The Sacketts have been in court fighting for the right to use their property since 2007. The Supreme Court heard the Sacketts’ case once before, ruling in 2012 that, contrary to EPA’s view, the Sacketts had the right to immediately challenge the agency’s assertion of authority over their homebuilding project. Now the Court will consider whether their lot contains “navigable waters” subject to federal control.

“The Sacketts’ ordeal is emblematic of all that has gone wrong with the implementation of the Clean Water Act,” said Damien Schiff, a senior attorney at Pacific Legal Foundation, which represents the Sacketts. “The Sacketts’ lot lacks a surface water connection to any stream, creek, lake, or other water body, and it shouldn’t be subject to federal regulation and permitting. The Sacketts are delighted that the Court has agreed to take their case a second time, and hope the Court rules to bring fairness, consistency, and a respect for private property rights to the Clean Water Act’s administration.”

In hearing the Sacketts’ case, the Court will revisit the 2006 opinion it issued in Rapanos v. United States, another case litigated by Pacific Legal Foundation. In that case, a divided Court left unclear which wetlands are under the federal government’s jurisdiction.

It’s beyond absurd that the Sacketts have had to spend 15 years dealing with a federal agency just to build a house on a residential-sized tract of land with no connection to interstate waterways. If environmentalists want to start tearing their hair out over a potential Supreme Court decision that guts WOTUS, they should direct their ire to the office-holders that allowed this travesty to continue, especially for a full decade after the Supreme Court warned everyone to fix the problem. It’s long past time to strip federal agencies of their ability to act in arbitrary and capricious manners based on legal ambiguities that make practically everything a federal case.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member