Alternatively, pollsters could just do their jobs better. Monmouth pollster Patrick Murray wrote a mea culpa today for missing the New Jersey gubernatorial race by a country mile, apologizing to both candidates and their supporters for his failure. Perhaps, Murray proposes, pollsters should just sit out the final few weeks of election cycles in the future:

I blew it. The final Monmouth University Poll margin did not provide an accurate picture of the state of the governor’s race. So, if you are a Republican who believes the polls cost Ciattarelli an upset victory or a Democrat who feels we lulled your base into complacency, feel free to vent. I hear you.

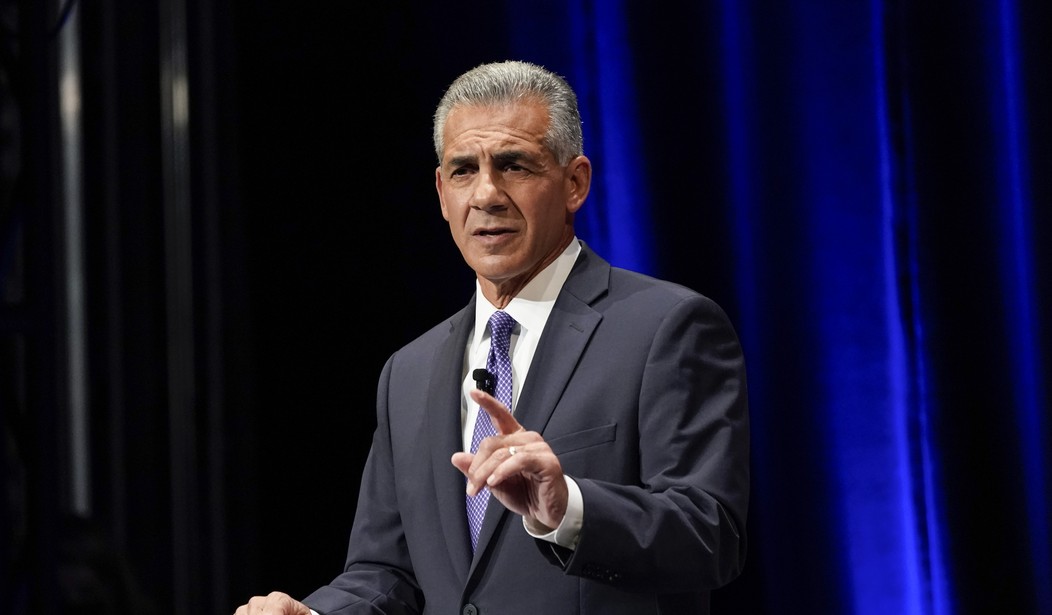

I owe an apology to Jack Ciattarelli’s campaign — and to Phil Murphy’s campaign for that matter — because inaccurate public polling can have an impact on fundraising and voter mobilization efforts. But most of all I owe an apology to the voters of New Jersey for information that was at the very least misleading.

I take my responsibility as a public pollster seriously. Some partisan critics think we have some agenda about who wins or loses. I can only assume they have never met a public pollster. The thing that keeps us up at night — our “religion” as it were — is simply getting the numbers right.

I’m not aware of people complaining about partisan bias regarding Monmouth. Some conservatives think Quinnipiac has a Democrat lean, but most of the complaints about partisanship are aimed at media polling, not independents and academics. FiveThirtyEight rated Monmouth an A pollster (before the election) based on polling to outcomes while detecting a D+2.1 bias — significant, but not as much as Morning Consult’s D+2.9, for instance (they get a B rating).

Besides, Monmouth is hardly the only pollster or poll observer who blew it in New Jersey. The Murphy-Ciattarelli contest was barely on anyone’s radar prior to this week, and the most remarkable aspect of the polling was the dearth of it in the race. RCP didn’t have enough to get an aggregate average until near the end, with the final average coming in at Murphy +7.8. At the moment, the results appear to be Murphy +2.3%, which is a miss but not by a yuuuge amount — although Monmouth’s nine-point miss is certainly the worst in the small field.

The aforementioned FiveThirtyEight didn’t think the race was competitive, either:

It may be positioned in a smaller typeface below Virginia on the Election Day marquee, but the New Jersey gubernatorial election could prove more interesting than we might have expected a few months ago. The contest between incumbent Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy and Republican Jack Ciattarelli, a former state assemblyman, had mostly simmered on the backburner as Murphy held polling leads of more than 10 points in nonpartisan polls up through August. However, as Biden’s ratings have tumbled, polls suggest the New Jersey contest might be a bit closer than it was before, although Murphy remains a substantial favorite to win.

Last week, a survey from Monmouth University — which calls New Jersey home — found Murphy leading by 11 points among registered voters, with the incumbent leading by 8 to 14 points in its likely voter model — a smaller advantage than in Monmouth’s previous polls (9 to 19 points). Additionally, a Stockton University poll found Murphy ahead by 9 points among likely voters, while a Fairleigh Dickinson University survey of registered voters put Murphy up by 9 points, but the pollster didn’t release a likely voter figure. But another recent nonpartisan survey, from PIX 11/Emerson College, found a closer contest with Murphy ahead by about 4 points among likely voters.4 The latest Monmouth and Emerson polls found Murphy remains more popular than not, however, as Monmouth put his approval at 52 percent and his disapproval at 39 percent, while Emerson found 49 percent had a favorable view of the governor versus 47 percent who had an unfavorable impression.

Nevertheless, when Murray falls on his sword, he makes sure he hits the ground:

While pundits and the media are hardwired to obsess on margins, we pollsters bear some responsibility too. Some organizations have decided to opt-out of election polling altogether, including the venerable Gallup Poll and the highly regarded Pew Research Center, because it distracts from the contributions of their public interest polling. Other pollsters went AWOL this year. For instance, Quinnipiac has been a fixture during New Jersey and Virginia campaigns for decades but issued no polls in either state this year.

Perhaps that is a wise move. If we cannot be certain that these polling misses are anomalies then we have a responsibility to consider whether releasing horse race numbers in close proximity to an election is making a positive or negative contribution to the political discourse.

There may be something to this argument, but only if these polling failures are truly unsolvable. That doesn’t appear to be the case, not even in New Jersey; Trafalgar scored it pretty closely, well within the margin of error, after all. Besides, candidates will certainly continue to use polling as part of their campaigns. Why should voters not have access to similar information, with the obvious caveat that they should — as they always should — consider them in the context of imperfect sampling and as momentary snapshots in time? If anyone’s dissuaded from voting on the basis of a poll, it’s probably safe to assume they’re not terribly committed to the process in the first place. That’s not Monmouth’s fault or issue.

I’d rather have the information and have people assume I’m an adult who comprehends how to use it properly, rather than otherwise.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member