If COVID hysteria did nothing else good, it did lay bare just how politicized science has become.

Having grown up around scientists I have a rather nuanced view of scientists. The very best scientists, or should I say the most productive scientists, have enormous egos and have as much desire to have an impact on the world as any other group of talented and ambitious people.

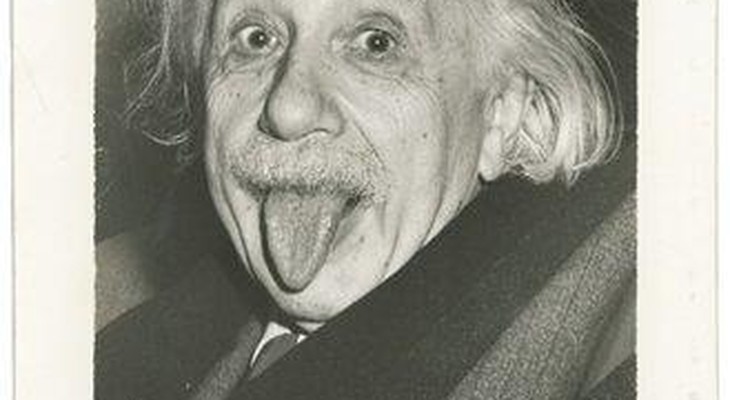

Far from being geeks plugging away in a lab letting experiments simply guide them wherever the evidence leads, all the scientists who are considered “great” have some form of charisma that lures others to follow them. Think of Einstein, who is widely regarded as the greatest scientist of the modern era and is known by nearly everyone. He is an icon.

His reputation is deserved–he revolutionized our view of the universe–but much of his fame and cultural influence rests in his ability to create an image that was larger than life.

I have always thought of Neil deGrasse Tyson as being in this category. He must be a smart guy, but no potentially great astronomer runs a planetarium. I’m sorry, but that is just a fact. He is a public intellectual and now a professional “expert,” but science isn’t his deal. He is in it for the fame and influence, and more power to him.

Fauci is in this category as well. He is a bureaucrat, and obviously great at that job. Bureaucrats are busybodies who tell people what to do, and Fauci is great at doing that because he sells himself as a scientific authority and borrows the legitimacy that comes from that. He does horrible things with his power but is superb at getting and exercising it.

There is a large cohort of scientists in this mold, and many of them wind up in positions to make your life difficult or shape the public perception of what The Science™ says. This has been true for a very long time.

“Public health” officials and health bureaucrats are very often in this mold. Not always–some are happy to do the work of keeping people healthy, but many lust for influence and do what it takes to have it. They revel in the act of power, not in the results of doing good things.

A great example of this is our new CDC Director Mandy Cohen, who gleefully explained just how arbitrary the decisions were made during COVID:

The CDC can start winning trust back by replacing the current @CDCDirector with someone who cares about making public health about science again, and not about what your girlfriends tell you on the phone. https://t.co/aQJx9gCwyq pic.twitter.com/O2IydT8mnX

— Kevin Bass PhD MS (@kevinnbass) September 18, 2023

She sounds like a schoolgirl gossiping about how she screwed with a guy’s life for fun, because that is what she was, just on a larger scale.

I went on this riff after reading an article in Quillette by Epidemiologist Geoffrey Kabat the author of “Getting Risk Right: Understanding the Science of Elusive Health Risks.”

Kabat is a researcher. Earlier in his career, he did a study with another respected epidemiologist on the effects of second-hand smoke on cancer rates. The study, which came out 20 years ago, undermined the narrative being pushed by the public health establishment that second-hand smoke is deadly and causes cancer. If you recall, there was a huge and successful push to ban indoor smoking at the time, and rather than focusing on the fact that nonsmokers often hate to be around smokers, public health folks tried to scare everybody by claiming it caused cancer.

Kabat had done a lot of research on cancer going back to the 80s and wanted to find out if it was true. His research in collaboration with another epidemiologist suggested that the risks were minimal to nonexistent according to the data, and that shouldn’t really surprise anybody. Smokers inhale concentrated cigarette smoke directly into their lungs; secondhand smoke is highly diluted and while unpleasant it really isn’t deadly.

The study was published in the British Medical Journal, and all hell broke loose. The science was sound, but inconvenient. It ran counter to the prevailing narrative and even prior to publication the attacks poured in.

The issue was not the science, the evidence, or the quality of the work. They were ad hominem and based on the failure of the study to say what was required of all right-thinking people.

The publication caused an immediate outpouring of vitriol and indignation, even before it was available online. Some critics targeted us with ad hominem attacks, as we disclosed that we received partial funding from the tobacco industry. Others claimed that there were serious flaws in our study. But few critics actually engaged with the detailed data contained in the paper’s 3,000 words and 10 tables. The focus was overwhelmingly on our conclusion—not on the data we analyzed and the methods we used. Neither of us had never experienced anything like the response to this paper. It appeared that simply raising doubts about passive smoking was beyond the bounds of acceptable inquiry.

Research going back many decades has shown a strong dose-related risk of cigarette smoking. People who smoke little or not at all have few risks associated with tobacco smoke; those who smoke a lot have a large risk.

However, the research on second-hand smoke was separated out from other tobacco smoke-related research–not necessarily for bad reasons–and that distorted the incentives scientists experience.

We have to bear in mind that scientists are human, and it is only human to want your results to be meaningful and to attract attention. Positive results are the currency of science and are essential to future grant support and career advancement. Furthermore, positive findings are simply more psychologically satisfying to both researchers and the general public than findings of no association. The issue of passive smoking should have been examined in the context of all that is known about the well-studied topic of cigarette smoking. Instead, treating it as a thing apart led to all sorts of distortions. So, how are we to guard against findings which appeal to our deepest fears but that never seem to receive solid confirmation in spite of repeated attempts?

Finding the association between smoking and cancer was a major deal; refining that research over time added to the overall fund of knowledge.

Once you separate out the question of tobacco’s effects on non-smokers the incentives suddenly change: any normal person would want to find a similarly dramatic result. Hence any study suggesting a correlation gets hyped, and any suggesting that the dose of the poison is too small to make an impact is a dud.

And if that dud undermines a political agenda, it needs to be destroyed. Not for scientific reasons–the BMJ, which at the time was still a science journal, published the paper because it was good science that was peer-reviewed–but because it violated the Narrative.

People wanted to find an association, for a variety of reasons. “Secondhand smoke kills” is a much more powerful argument than “being around smokers sucks.” And scientists wanted to find important results that increased their fame, power, and funding.

In that context attacking a scientific finding that might be true but inconvenient made sense.

Science is very often like this in the real world. Far from being an objective activity done by disinterested people, it is done by human beings, and human beings are flawed.

That is not a knock on science; it is just a reason to always be skeptical. As any good scientist would be.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member