The United States military is the most advanced in the world. High technology weapons and delivery systems get all the press, but what makes the US military special is it mastery of logistics and its ability to integrate systems in a way to deploy what you need, when you need it, in a manner that it can have maximum impact.

One of the keys to the military’s success has been the venerable C-130, a transport aircraft that is nearly 70 years old. First deployed in 1954, it has gone through many iterations, but like the DC-3 it is a proven platform that has served reliably for decades and adapted to the needs of its users. It has outlasted nearly everything the military has developed, and as with the B-52 you can expect it to outlast aircraft that are on the drawing boards.

The Air Force has found a new use for the platform: the Rapid Dragon weapons program, which will soon turn American and allied transports into bombers able to deliver swarms of cruise missiles and potentially JDAMS to the battlefield. Not intended to enter contested airspace as fighters and strategic bombers do, the Rapid Dragon system can rapidly turn C-130s into bomb trucks that can threaten adversary targets including anti-aircraft systems from a distance, cheaply.

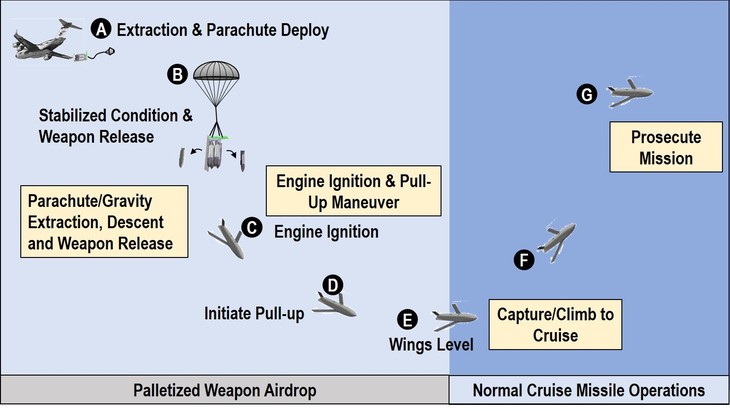

Rapid Dragon is a palletized weapons delivery system; Rather than putting weapons on the wings or inside a bomb bay, cruise missiles are installed in a pallet that gets air dropped out the back of the transport aircraft. The pallets are configurable, have their own control boxes linked to a control networks (meaning that the aircraft is a “dumb” delivery system for “smart” weapons). It is the realization of an idea with a 50-year history: the bomb truck.

The first iteration of the bomb truck I ever heard of was using a converted 747 as a carrier for cruise missiles. The idea was never developed into a weapons system, as has been the case with every other proposal to use non-special purpose aircraft to deliver bombs and missiles.

What makes Rapid Dragon special is how cheap it is to test and deploy. There isn’t a huge up-front cost and hence it avoids the massive political barriers that bedevil weapons programs. Large bureaucracies tend to hate small, unsexy programs that don’t advance careers.

There’s nothing sexy about a C-130, and with a 2-3 years program period nobody is going to make General from Major running this weapons program.

But it might just change the balance of power in the Pacific, where China’s A2-AD strategy will take a hit if we can deliver massive amounts of ordinance with cheap and plentiful aircraft that are very inexpensive to fly. B-2s are the opposite, and the B-21 is years from deployment. The NGAD will be enormously expensive and while expected to be a capable platform, it will not be able to deliver massive amounts of ordinance on target.

B-52s and and the B-2s require long and well serviced runways, while C-130s can deploy from shorter and less groomed runways. The C-130 as a weapons platform may be unsexy, but it could be extremely useful.

The Chinese are reportedly keeping an eye on the program for obvious reasons:

The Chinese military is reportedly alarmed by a new tactic being employed by the US Air Force. During a live-fire exercise over Norway, the service showcased the ability to deploy Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles (JASSM) from cargo aircraft, such as the Lockheed Martin C-130J Super Hercules, via the Rapid Dragon Palletized Weapon System.

Developed by the US Air Force and Lockheed, Rapid Dragon is an airdropped palletized and disposable weapons module that provides unmodified cargo aircraft, such as the C-130J, Boeing C-17 Globemaster III and Lockheed MC-130, with the ability to deploy an array of flying munitions, such as cruise missiles. Slowed by parachutes, the pallets release their missiles through the use of an attached electronic control box.

The concept comes from the 10th-century Chinese volley-firing siege weapon, Ji Long Che, which allowed for the launch of multiple long-range crossbow arrows from a safe distance. Along with allowing the US Air Force to initiate attacks from outside of dangerous areas, it means cargo aircraft can be temporarily repurposed as standoff bombers, a cost-effective measure.

JASSMs can be deployed from other aircraft, of course, and were designed to do so. But the ability to deploy dozens at a time in a swarm and with no warning could be a game changer. A C-130 could easily fly into an airstrip, delivery a cargo, and upon takeoff be equipped to deploy cruise missiles.

All the components making up Red Dragon are held within the pallet, which can be dropped from a height of just 3,000 feet. It’s also believed the weapon system could be used to target the vulnerabilities of other countries’ air defense systems – think the S-300 and S-400 used by Russia – during swarm tactics missions.

Presently, Rapid Dragon is able to deploy the AGM-158 JASSM, a low observable standoff air-launched cruise missile, and its variants, and is able to produce a payload capacity of between 4,000 and 9,900 kilograms. Depending on the variant of cruise missile, its range can be anywhere from 80 to 1,900 kilometers.

Following the successful live-fire demonstration in November 2022 as part of US Special Operations Command Europe exercise ATREUS 22-4, Lt. Gen. Jim Slife, Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) commander, said Rapid Dragon is “really easily exportable to our partners and allies around the globe that may want to increase the utility of their air force.”

Lt. Col. Valerie Knight, 352nd Special Operations Wing (SOW) mission commander, added, “An MC-130J is a perfect aircraft for this capability because we can land and operate from 3,000-foot highways and austere landing zones whereas a bomber cannot.”

The US Air Force plans to carry out another test in February 2023, this time over the Gulf of Mexico at the Eglin Air Force Base Over Water Test Range in the western Florida Panhandle. This demonstration will involve an unspecified cruise missile armed with a live warhead.

The ability to export serious bomber capability to our allies–who have no capability similar to the US bomber fleet–is also a game changer. If Japan and Australia suddenly become offensive threats to China, that complicates their strategic calculations exponentially. Especially when you consider that the C-130 need not deploy from major airports or airbases, as would a strategic bomber.

The development of Rapid Dragon has reportedly alarmed Chinese military experts, according to an article in the Science and Technology section of China National Defense News, a sister publication for the PLA Daily. The latter serves as the mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Military Commission.

In the article, author Xi Qizhi notes that cargo aircraft are able to carry out more combat sorties that typical bombers and are much more difficult to track. He also suggests that such aircraft could conduct strike missions following the transportation of goods to the front, providing a dual-purpose for necessary supply trips.

“The agility of the US military’s distributed method for strike missions and the suddenness of those strikes will increase immensely,” Xi writes.

These concerns were echoed by Derek Solen, a US Air Force civilian researcher specializing in Chinese aerospace studies, in an article for The Jamestown Foundation. “The PLA likely regards Rapid Dragon in particular as a credible threat,” he writes. “The PLA is likely to regard the seriousness of that threat as significantly greater if Rapid Dragon is shared with American allies.”

The Air Force has 200 or so C-130s, and the aircraft is used by other air forces and in the US National Guard as well.

The US military has many strengths, but cost-efficiency and rapid development of weapons systems and capabilities hasn’t been one of them since the 70s. We tend to associate the US with innovation and the military with high tech, but the fact is that the military procurement process is a total mess. The system is highly bureaucratized, politicized, and grossly slow and inefficient.

An example: the Air Force decided to buy its first jet-powered refueling aircraft in 1954. After a competition, Boeing’s KC-135 was awarded a contract in 1955; the first plane was delivered in 1956. It has been the backbone of our refueling fleet ever since.

In 2001, the United States decided to replace its oldest KC-135s with a newer, more capable tanker. It held a competition, eventually choosing a Boeing 767-derivative. The selection process was scandal-plagued and the original contract was canceled in 2006. The Air Force had a new competition, eventually choosing Boeing again in 2011 as the provider of the KC-46, which is also a 767 derivative.

After years of delay the KC-46 is still not combat ready, and the latest estimate is that it may be by the end of this year. The aircraft is still plagued with multiple issues, although it is now capable (if necessary) of refueling some military aircraft if necessary during a war. It still cannot refuel America’s most advanced aircraft safely. Boeing has lost at least $5 billion on the program.

In other words, from identifying the need to delivering a working aircraft has taken 22 years so far, and the process is not complete.

The U-2 was proposed in 1953, and entered testing in 1955. The SR-71, the fastest aircraft ever flown, took 3 years from proposal to delivery of the first aircraft. Now it takes decades to deliver a platform.

Obviously the challenges of integrating newer electronics are different today, but 22 years plus to develop a tanker replacement? That is the result of a fundamentally broken process.

That’s why I see the Rapid Dragon program as such a welcome development. Not only is the capability great to have and a major force multiplier, but the process of development is, in today’s military, revolutionary.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member